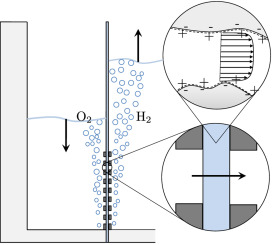

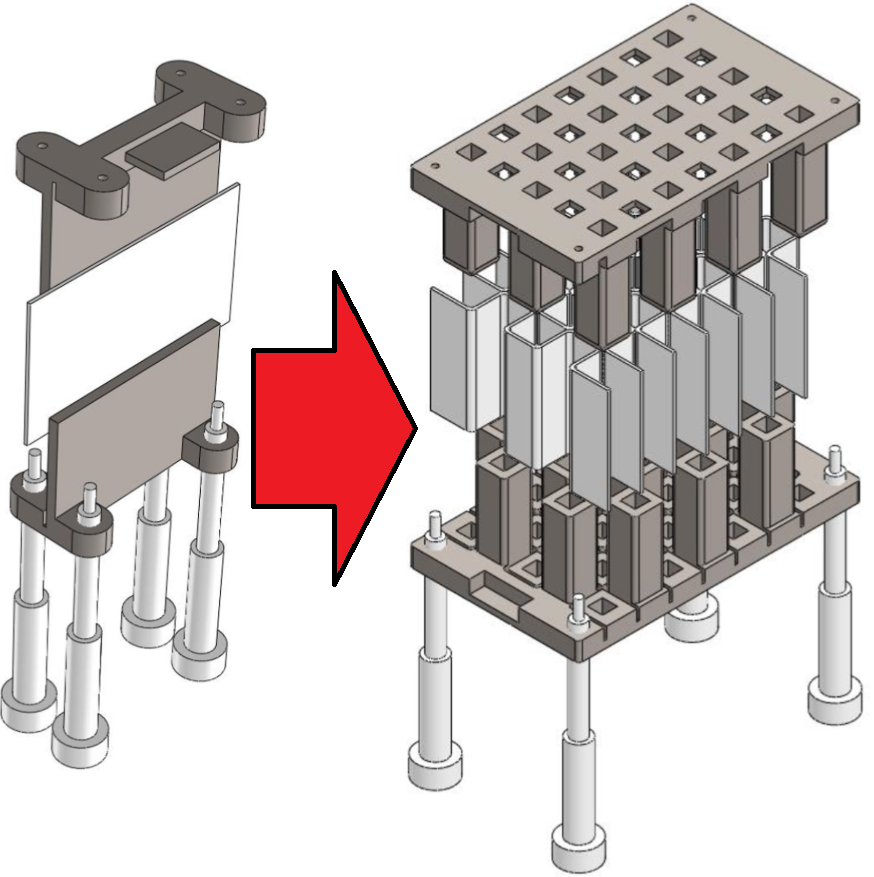

Hydrogen bubbles generated at an electrode of a water electrolyzer rise due to their buoyancy and set the surrounding liquid into motion. Alternatively, the bubbles make the mixture lighter causing it to rise – similar to the hot fluid near a heated plate. An important difference with this well-studied ‘thermal natural convection’ case is that the gas fraction has a certain maximum, below one, which influences the plume in a previously unknown way. This understanding is important, for example, to describe heat and mass transport. Knowing the bubble layer thickness is also useful to properly choose the dimensions of an electrolyzer.

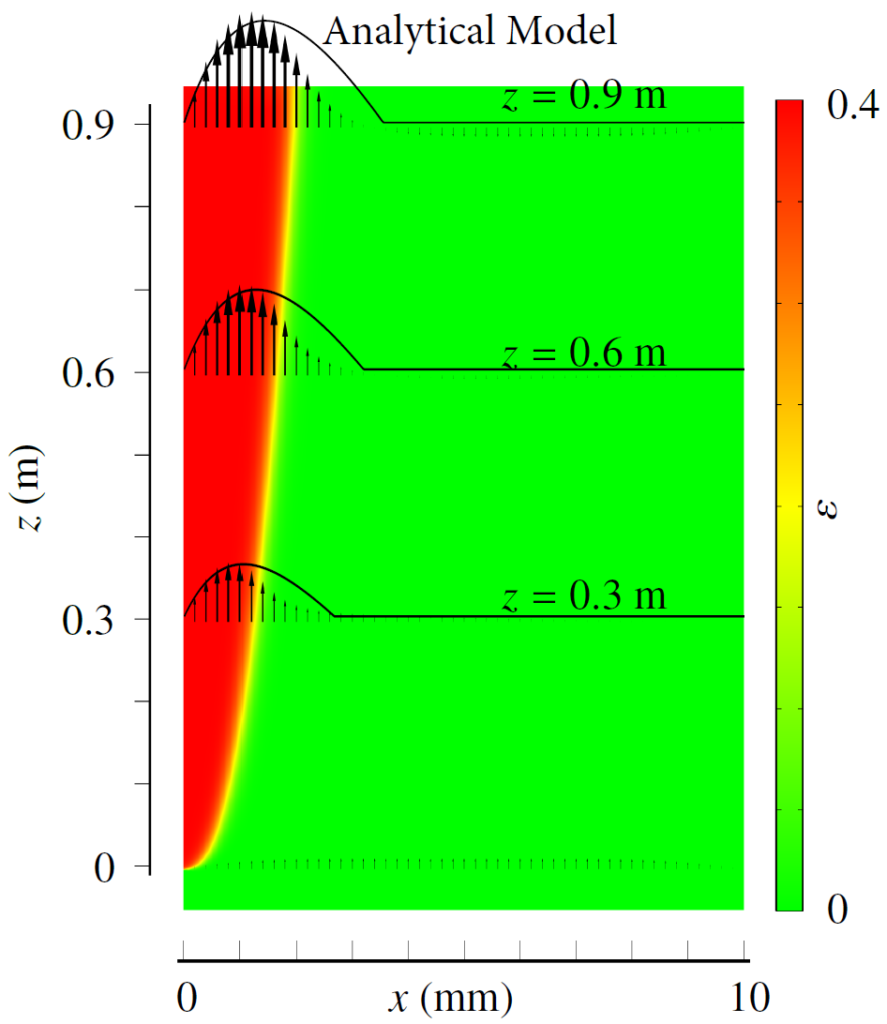

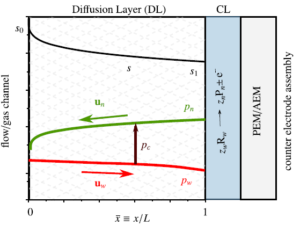

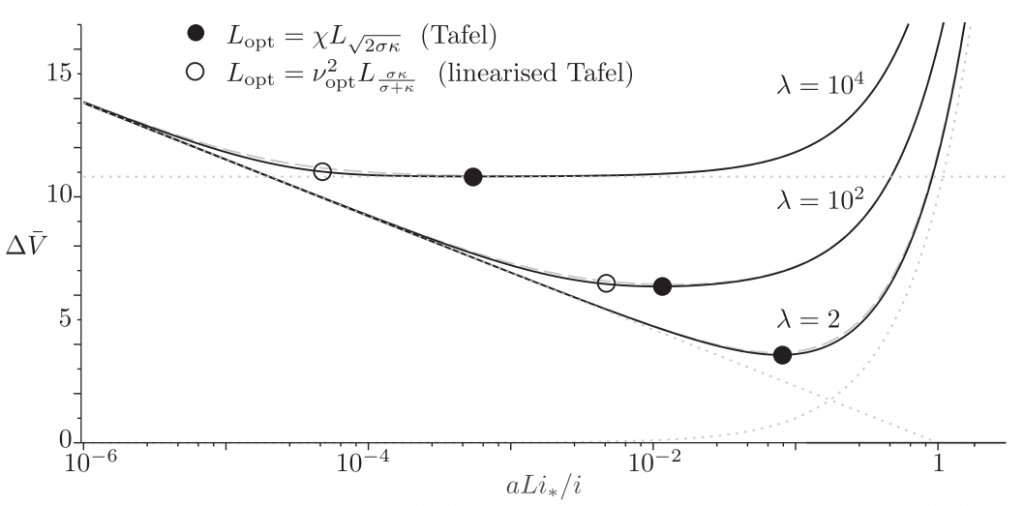

Therefore, we made an analytical model to describe the plume thickness and associated velocity profile. To validate this model, we performed computational simulations. A comparison between the analytical and computational models is shown in the below figure. The resulting formulas will be very useful for scaling up electrolyzers and understanding the effect of height and current density on gas hold-up and heat transport.

Rajora, A., & Haverkort, J. W. (2023). An analytical model for the velocity and gas fraction profiles near gas-evolving electrodes. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy.

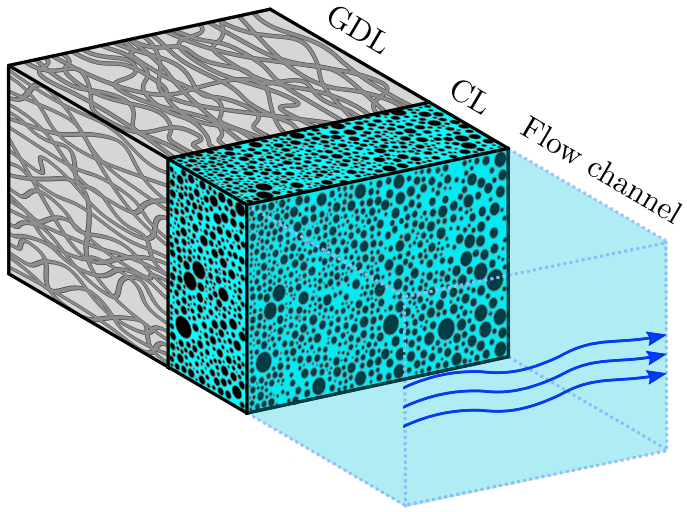

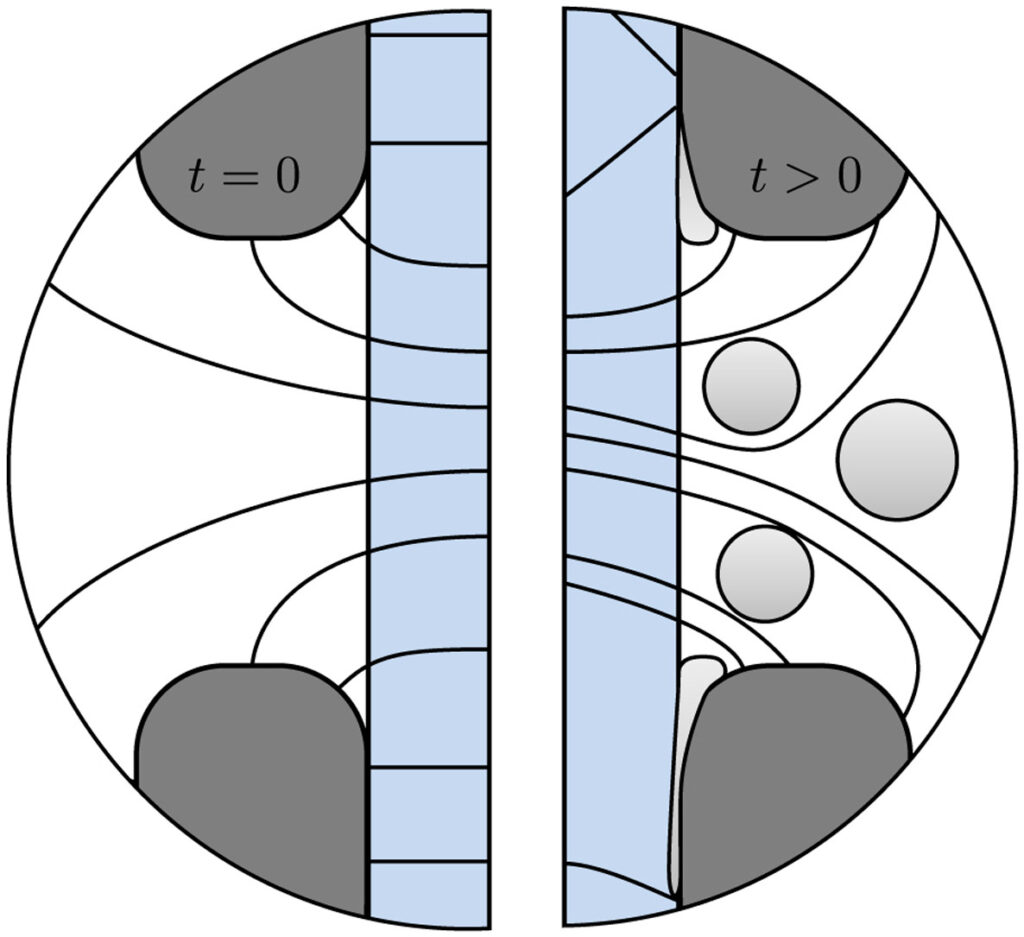

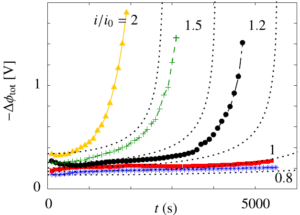

The dimensionless electrode overpotential versus electrode thickness. For the notation used see:

The dimensionless electrode overpotential versus electrode thickness. For the notation used see: